If there’s one thing I really enjoy, it’s a page-turner of a book and, Dan Brown’s latest Robert Langdon mystery, Origin, is certainly that. Park your bottom, pour a coffee, wine or beverage of choice, put on the lamp, and begin…

Once again, the quiet, Mickey-Mouse watch-wearing Professor of Symbology, Robert Langdon (and now I always picture the wonderful Tom Hanks), is in the wrong place at the right time – the right time to thrust him into the middle of a murder investigation with potentially catastrophic, future-of-humanity-is-at-stake, life-changing consequences.

Once again, the quiet, Mickey-Mouse watch-wearing Professor of Symbology, Robert Langdon (and now I always picture the wonderful Tom Hanks), is in the wrong place at the right time – the right time to thrust him into the middle of a murder investigation with potentially catastrophic, future-of-humanity-is-at-stake, life-changing consequences.

Attending the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, to hear a former student of his, Edmond Kirsch, deliver a speech he claims “will change the face of science forever”, by delivering the answers to two fundamental questions that have perplexed scientists, religious minds and philosophers for centuries, what Langdon doesn’t expect is the murder and mayhem that unfolds. Though, really, on past experiences (I’m thinking Angels and Demons, The Da Vinci Code, The Lost Symbol and Inferno) maybe he should.

After all, Edmond, a computer and high-tech genius who has made dazzling and accurate predictions for over twenty years that have gained him a global cult following, is no stranger to controversy. Not afraid to poke a religious hornet’s nest, the book opens with Edmond baiting three religious leaders by allowing them a preview of what he intends to release. For such a smart man, this seems like a dumb move as there are those among the faithful who will do anything to ensure his discovery is never revealed.

When the presentation to the world goes horribly wrong, it becomes a race against time as Professor Langdon (and his trusty watch), a beautiful female side-kick (is there any other kind?) and a very sophisticated piece of technology, work to ensure Edmond’s discovery is made public. As much as the good Professor and his helpers seek to do what they believe is right, there are those working against them who believe the same thing and will stop at nothing to ensure they fail, even if it means more bloodshed.

In the meantime, all eyes are turned to Spain – as conspiracy theories and theorists, a growing media pack, denizens of the internet and a digital and real audience simultaneously commentate upon what is happening.

Gaudi’s, Sagrada Familia

There’s no doubt, Brown has perfected the art of making sure his reader is hooked. Fast-paced, filled with didactic speeches (that are nevertheless interesting and entertaining), that reveal religion and science to be both juxtaposed and yet, not as polemically situated as one might think, Langdon’s mission is, indeed, an ideological game-changer… or is it? Tapping into the zeitgeist, Brown ensures that the questions tormenting many in the world at present such as the role of religion and faith in a technologically-savvy, rational world that constantly seeks proof and wonders can these two oppositional ways of thinking ever find common ground, are asked. Required to suspend your disbelief (which is fine), there are some strange plot points that frustrate rather than illuminate, and so impact upon the overall believability, even within this genre, of the sometimes OTT actions and consequences. Mind you, the glorious descriptions of Antoni Gaudi’s works does go someway to compensating.

As is often the case, the journey to uncover answers is often more exciting and revealing than the destination. Still, there is much to enjoy about a book that excites the mind and the mind’s eye, turns an academic into, if not a super-hero, then certainly a hero and, it seems, religious authorities into villains while concurrently overturning a great many expectations. There’s also a satisfying twist that many might see coming, but that doesn’t reduce the impact.

Overall, another fun, well-paced, Robert Langdon adventure, replete with groans, dad-jokes, and some fabulous facts. I hope he takes us on a few more.

me, which covers the years Elizabeth was upon the English throne.

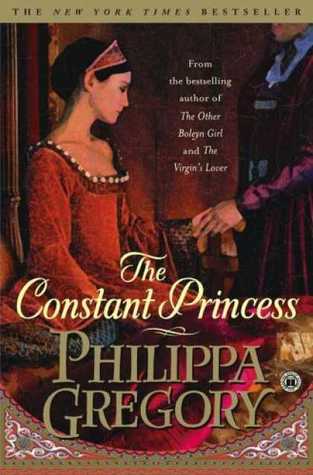

me, which covers the years Elizabeth was upon the English throne. often silent and very religious presence in many fictive accounts, a woman who stood by Henry for over twenty-seven years before her marriage to him was ended in tumultuous circumstances, resulting in not just the rendering of her only living child to Henry, Mary, a bastard, but the over-turning of the Catholic faith in England, Catherine as a person remains an unknown quantity. She also tends to hover in the margins when it comes to Henry’s reign and his other wives and the fate that befell them, especially Anne Boleyn, the women who took Catherine’s throne and husband and whose daughter went on to become the “Virgin Queen”, Elizabeth 1st.

often silent and very religious presence in many fictive accounts, a woman who stood by Henry for over twenty-seven years before her marriage to him was ended in tumultuous circumstances, resulting in not just the rendering of her only living child to Henry, Mary, a bastard, but the over-turning of the Catholic faith in England, Catherine as a person remains an unknown quantity. She also tends to hover in the margins when it comes to Henry’s reign and his other wives and the fate that befell them, especially Anne Boleyn, the women who took Catherine’s throne and husband and whose daughter went on to become the “Virgin Queen”, Elizabeth 1st. and everyone in his life. He is also an expert swordsman and brave soldier who in the past accompanied Robert Devereux, the Earl Of Essex and the Queen’s young favourite, to Spain and was by his side during other skirmishes, thus earning praise and a reputation as loyal and courageous.

and everyone in his life. He is also an expert swordsman and brave soldier who in the past accompanied Robert Devereux, the Earl Of Essex and the Queen’s young favourite, to Spain and was by his side during other skirmishes, thus earning praise and a reputation as loyal and courageous. nglish geographical growth and plans for domination (I think one of the terms used was “Seeding” – but that may have been another book) it soon becomes clear that Wilson is being deliberately provocative in order to insist the reader suspend contemporary judgement and the sins of “isms” (racism, sexism, classism etc.): that we view the Elizabethan world through Elizabethan eyes, politics, religious upheavals and belief systems and that we, as far as possible, withhold judgement (and for the sake of better words, “politically correct” assumptions and thus criticisms about actions and decisions – though this is very, very hard) and instead seek to immerse ourselves in this rich, brutal, decadent, paranoid, artistic and amazing time.

nglish geographical growth and plans for domination (I think one of the terms used was “Seeding” – but that may have been another book) it soon becomes clear that Wilson is being deliberately provocative in order to insist the reader suspend contemporary judgement and the sins of “isms” (racism, sexism, classism etc.): that we view the Elizabethan world through Elizabethan eyes, politics, religious upheavals and belief systems and that we, as far as possible, withhold judgement (and for the sake of better words, “politically correct” assumptions and thus criticisms about actions and decisions – though this is very, very hard) and instead seek to immerse ourselves in this rich, brutal, decadent, paranoid, artistic and amazing time.