This newest biography of Geoffrey Chaucer, the medieval poet, diplomat and court official is a tour de force. Whereas other biographies of the poet have examined what can be gleaned of this amazing man’s life from various contemporary documents, art, funeral effigies, family trees, etc. as well as his marvellous fictive works, Marion Turner starts with the premise that one writes what one knows, drawing on the familiar to compose fiction and fabliaux. Assuming this was also what Chaucer did, even when translating and appropriating other sources, she uses his works as a primary source (as well as many, many relevant contemporary documents and the work of chroniclers) to make sense of the various events in his life. Afterall, whether it was to whom he dedicated a piece of work or a character like the real-life Harry Baily owner of the Tabard Inn in Southwark who hosts the Canterbury Pilgrims, Chaucer wrote what and who he knew. As a consequence, this biography not only takes on a rich and new relevance as Turner invites us to examine everything Chaucer worked upon and rewrote and reworked, such as his tribute to the Duchess, Blanche Lancaster, The Book of the Duchess, or his translation and retelling of The Romance of the Rose or his unfinished and arguably greatest or best-known work, The Canterbury Tales, as a critique of both his own life and the times. Further, as Turner delves deeper into Chaucer’s works, she also deconstructs them and their meaning, providing another layer of denotation to not just Chaucer’s life, but his poetry. So this book is both biography and a wonderful literary analysis.

The title alludes to the fact that though Chaucer was a Londoner by birth and for most of his life, a man of the court, streets and castles and estates beyond, he was also very much a man of the world, traveling to various foreign ports for king and country, negotiating royal marriages, loans, fighting wars, able to speak other languages (naturally, French and Latin, but also Italian), meeting with despots, mercenaries and nobles. He also encountered the works of some of the greatest writers of the era and allowed them to influence his writings – Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio among them. He was perceived as a man of worth – not because of his birth, but because of his formidable talents and skills and his ability to dine with princes and paupers. So much so, he was ransomed for the kingly sum of 16 pounds when he was captured by the French when still very young. He was a man of the world as much as he was of the kingdom of his birth.

Patronised by John of Gaunt and paid annuities by three kings, Chaucer bore witness to many great and tragic events of his age: royal ascensions, falls, death, births, the plague, wars, famine, riots and rebellions as well as unjust and just behaviour. Married to Philippa, the sister of John of Gant’s infamous mistress and later wife, Katherine Swynford, he was also close to the centre of power in more than physical ways. Chaucer witnessed the best and worst of human behaviour and relationships and among all walks of life – what love, war, power, avarice, lust etc can do to people, how it can bring out the best and worst – and never lost his fascination for writing about these and the people who experienced them.

Able to remain on the right side of the monarch and the powers surrounding him for most of his life, Chaucer, though famous within his own lifetime, also managed to fly under the sometimes very taut and tense radar surrounding his primary patron, Gaunt, who was variously accused of treason, plotting against the king and was, for an extended period, the most hated man in England as the peasants (and others) blamed him for all the country’s perceived ills. So bad did feelings run, that during the Peasants Revolt of 1381, and which it’s likely Chaucer witnessed from his rooms above Aldgate, Gaunt’s main residence, the palatial and beautiful Savoy, was utterly destroyed.

It’s testimony to Chaucer that, unlike other Lancastrian cronies during the 1380s and 1390s, he managed to stay in the king’s (Richard II’s) good graces and thus avoid punishment, exile or death when so many others failed. Turner beautifully extrapolates how and why this may have happened – in no small part due to Chaucer’s great understanding of human nature and ability to walk in others’ shoes regardless of birth, education, beliefs, and even sex – all of which we’re privy to through his works. Perhaps the greatest irony is that while Chaucer was able to describe in allegorical and rich detail the pathos, sadness and joy love can bring, and place in his character’s mouths all sorts of notions about amour and marriage, his own doesn’t appear to have been too successful.

Despite this, his children went on to accomplish things their middle-class father, the son of a vintner, could once have only dreamed and which Chaucer, with his focus throughout his works on “gentillesse” as a worthy quality, despite rank, would have nonetheless appreciated. Some of the greatest bloodlines, houses and nobles descend from Chaucer’s grand-children. But the greatest gift he left us, and which Turner mainly celebrates and helps us to appreciate even more, are his works. But it’s as the “father of English Literature” that he’s best remembered – the man who gave the English their own poetry and voice in their own language, with eloquence, imagination, humour and beauty.

This is a fabulous, erudite piece of scholarship that’s also beautifully written and easily understood. A wonderful addition to the Chaucer canon and a great read for anyone interested in history, poetry, literary analysis and, of course, the enigmatic, clever and always creative, Chaucer.

Isn’t it funny how, when you’re hooked on a series and the characters the writer has created, you develop a love/hate relationship with each new book? That’s what happens with me. I get so excited that a fresh instalment is there to lose myself in, then I absolutely hate it when I finish and have to wait for the next one!

Isn’t it funny how, when you’re hooked on a series and the characters the writer has created, you develop a love/hate relationship with each new book? That’s what happens with me. I get so excited that a fresh instalment is there to lose myself in, then I absolutely hate it when I finish and have to wait for the next one! Europa Blues, by Arne Dahl, was a really different kind of crime book, even in the genre I am so enjoying, the broadly termed “Nordic Noir.” Not realising this was book four in a ten book series, I picked it up, seduced by the synopsis on the back of the book which explains that his novel is about a series of crimes involving the grisly death of a Greek gangster, disappearing Eastern European prostitutes and the macabre murder of a famous Jewish professor. From the start, it was pretty clear to me that the police involved in the investigations had complex lives and histories to which I was only partly privy and which no doubt earlier books explored. But (and this is testimony to the strength of Dahl’s writing), at no point did I feel this disadvantaged me. Such was the power of the prose and the way the principal characters were presented and their back-stories hinted at, I felt I knew them and any gaps and omissions were filled. Better still, I cared about these people deeply.

Europa Blues, by Arne Dahl, was a really different kind of crime book, even in the genre I am so enjoying, the broadly termed “Nordic Noir.” Not realising this was book four in a ten book series, I picked it up, seduced by the synopsis on the back of the book which explains that his novel is about a series of crimes involving the grisly death of a Greek gangster, disappearing Eastern European prostitutes and the macabre murder of a famous Jewish professor. From the start, it was pretty clear to me that the police involved in the investigations had complex lives and histories to which I was only partly privy and which no doubt earlier books explored. But (and this is testimony to the strength of Dahl’s writing), at no point did I feel this disadvantaged me. Such was the power of the prose and the way the principal characters were presented and their back-stories hinted at, I felt I knew them and any gaps and omissions were filled. Better still, I cared about these people deeply. n backdrop.

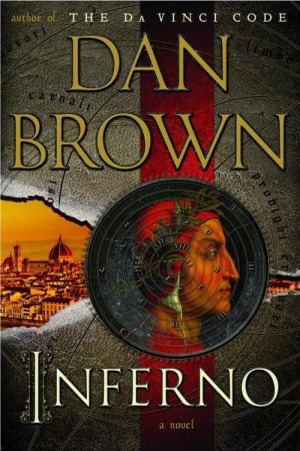

n backdrop. ory of how he got there or why. When strangers try to take his life and a beautiful and clever female doctor offers rescue and potentially some answers to the blanks his memory has become, Langdon jumps (literally) at the chance.

ory of how he got there or why. When strangers try to take his life and a beautiful and clever female doctor offers rescue and potentially some answers to the blanks his memory has become, Langdon jumps (literally) at the chance.